This winter, The Hudson Company salvaged lumber from a large 19th century barn in York Springs, PA, a rural farming community in Adams County about 15 miles northeast of Gettysburg. This part of Pennsylvania briefly gained notoriety as a health retreat thanks to the York Sulphur Springs, a summer resort that catered to clientele from Baltimore and Philadelphia, and even hosted George and Martha Washington in 1799. But the construction of the regional railroad shifted traffic away from this part of the state in the 19th century, and it has remained a largely rural enclave ever since. There’s a strong sense of history in this part of the state. Gettysburg was the site of a key battle of the Civil War, and today Gettysburg National Military Park is the most visited battlefield in the United States. Adams County is also the gateway to Pennsylvania Dutch country, and there are nearly 80,000 Amish people—the descendants of Swiss Protestant settlers who eschew modern technology—living in Pennsylvania today. Horse-drawn carriages with bright orange traffic safety signs on the back are a common sight here.

The landscape and architecture of other parts of Pennsylvania—Pittsburgh, Scranton and Philadelphia—were drastically transformed by mining and industry in the 19th and 20th centuries, but this part of the state remains pastoral and green. So it’s no surprise that Pennsylvania is one of the only states in America that has several styles of barn construction named after it. Robert F. Ensminger, an emeritus professor of geography at Kutztown University, developed a typology in his 2003 book The Pennsylvania Barn: Its Origin, Evolution, and Distribution in North America (Johns Hopkins University Press.) Ensminger explains that Pennsylvania’s unique barn architecture is the result of a blending of different European building traditions in collective response to the topography of the region. Immigrants from Germany, Switzerland and the British Isles brought with them the barn construction techniques of their countries of origin, and adapted their designs to suit the landscape they encountered here. He identifies three primary barn types: the Royer-Nicodemus Barn (1790—1900) which were built into hillsides and have overhanging forebays; the Sweitzer or Swisser barn (1730—1850) which are crib-type barns built from logs with overbays and asymmetrical gables; and the Extended Pennsylvania barn, which are taller and wider barns built later in the 19th century with features of the first two types.

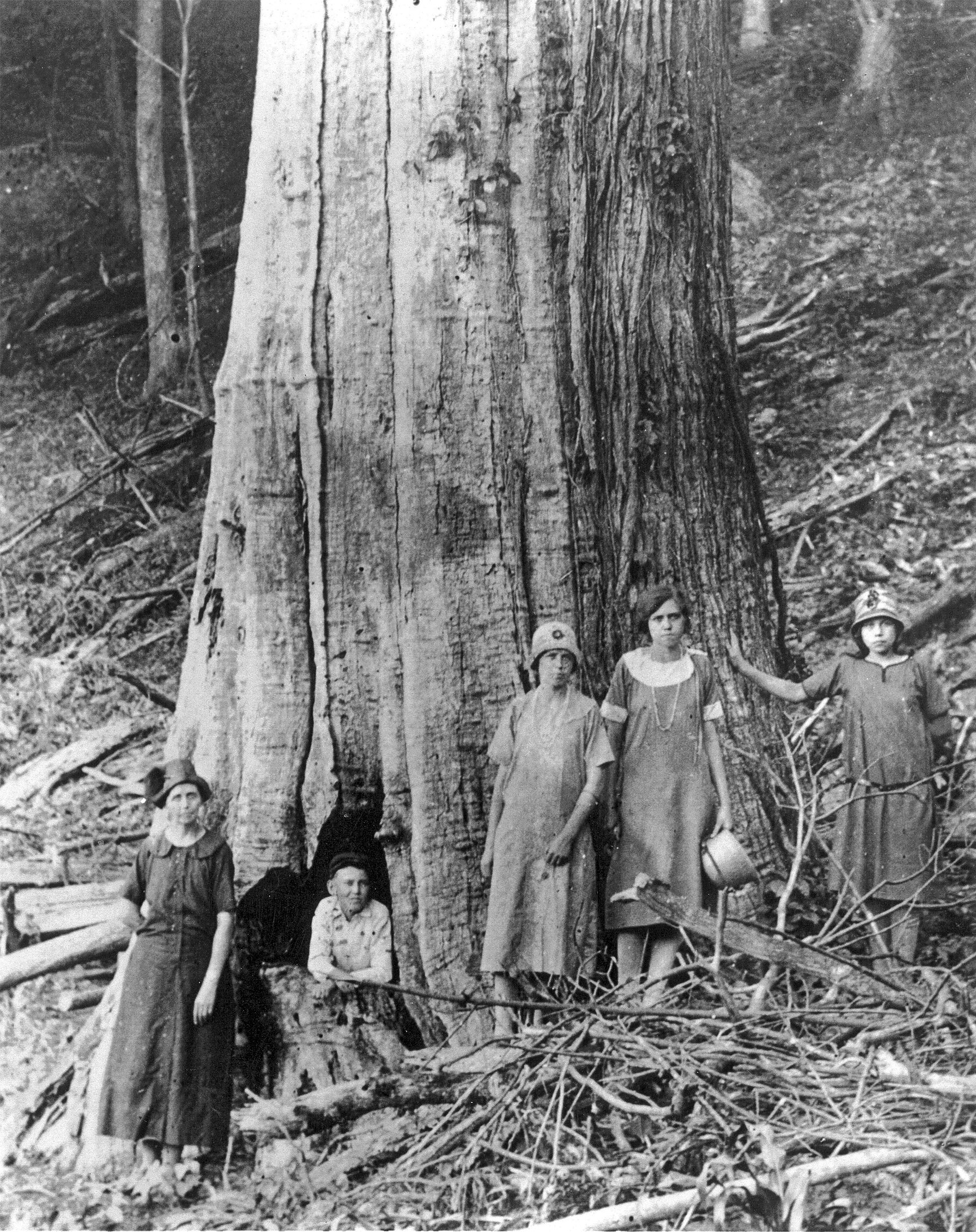

The York Springs structure that The Hudson Company recently salvaged was probably an Extended Pennsylvania barn. It has a forebay typical of the Royer-Nicodemus type, which allowed farmers to easily access both the basement and the levels above it. It also has an asymmetrical gable roof like a Sweitzer, so named for the barn Swiss design that likely inspired it. As farming technology improved and productivity increased in the mid-19th century, form followed function, and farmers built larger structures to accommodate livestock, feed, and equipment. The York Springs barn was three stories tall, and had high ceilings on its second level, with many intriguing features. Carved Roman numerals can be found on some of the beams—this may have been a technique for builders to note where each piece of lumber should go in the structure. The floors were built from wide planks. We refer to rustic wood that comes from the area where wheat was likely separated from the chaff as Oak Threshing. As it was deconstructed, the wood beams that supported the upper floor were exposed, revealing a complex, web-like system of interior struts. These are primarily hand-hewn White Oak, and tend to have wonderful characteristics and quirks like mortise holes and pockets. Now all that the wood has been salvaged in York Springs will become the foundational elements of homes and buildings across the United States, extending the life and reach of this centuries-old regional legacy, perhaps for generations to come.