If you’re familiar with the work of Wharton Esherick (1887–1970), you’re probably imagining the most famous spiral staircase in Pennsylvania right now. Built in 1930 to replace a traditional staircase, it’s tightly curled and elegantly carved from red oak, with a rustic form that appears to defy gravity. Its thick treads seem to float as they spiral around a curvy central column. They’re actually mortised in place and supported by tenons, but the lack of any supporting structure (apart from a mastodon tusk handrail that was added in the late 1940s) gives the staircase an air of magic. It’s just one example from a long career in which Esherick seemed to ask himself what he could do with wood, and never backed away from a surprising answer. Unorthodox solutions and clever workarounds abound in his unique home and studio in Paoli, PA, which is now the site of the Wharton Esherick Museum. And that makes sense, because he never trained as a woodworker; first and foremost he was an artist, and he was able to fashion wonders from any material, never letting the strictures of carpentry fence him in.

The Spiral Staircase in Wharton Esherick's home and studio, 1930.

Photo credit: ©LeslieWilliamson from Handcrafted Modern, Rizzoli, 2010.

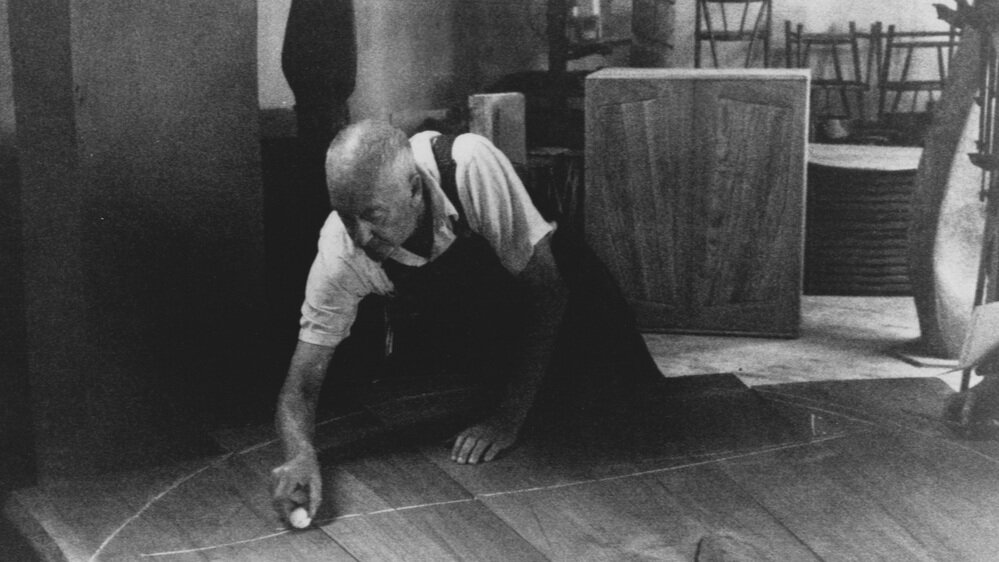

Wharton Esherick in his studio with his sculpture Oblivion (dated

1934.) Photo credit: c. 1934 by Emil Luks. Image courtesy of the

Wharton Esherick Museum.

Famous for saying “If it isn’t fun, it isn’t worth doing,” Esherick crafted furniture, made sculpture, designed lighting and interior fittings, and even whole buildings. He’s considered an icon of the Studio Furniture Movement of the mid-20th century, and having lived and worked in Bucks County, he’s also linked to a group of important Pennsylvania makers of his era: George Nakashima, Phillip Lloyd Powell, and Paul Evans. He came from a well-to-do Philadelphia family, and studied printmaking and drawing at the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art (now known as the University of the Arts), then painting at PAFA, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. He was discovering the world of painting just as American Impressionism was flourishing in Philadelphia and Bucks County. Esherick and his wife Letty settled in Paoli after finishing school and bought an historic farmhouse. Here he became interested in carpentry and the sculptural possibilities afforded by wood.

Esherick initially carved woodcuts—a natural outgrowth of his printmaking practice from art school—then he began making abstract sculptures from wood from in the 1920s. In 1926 his work was exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art. He then embarked on the long process of designing and building his own home and studio. And by the mid-1930’s, he was creating elaborate interior elements for local clients such as his famous doorway and fireplace for the Curtis Bok House. Considered some of his most important works, the dramatic doorway was meant to evoke the look of draping fabric, while the fireplace, which echoes Art Deco design but veers toward a more extreme, angular style, was inspired by the dramatic shadows cast by a roaring fire.

Fireplace and door by Wharton Esherick from the Curtis Bok House,

1935. Image courtesy of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

“A Pennsylvania Hill House” designed by architect George Howe for

the "America at Home" display at the 1939 World's Fair. Photo by Richard Garrison. Image courtesy of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Over the next several decades, his work was hard to pin down stylistically. Some works were crisp and geometric like the Bok House architectural elements. Others, like his own staircase and the biomorphic, abstract forms he sculpted, were soft and organic. In 1940, he created a suite of furniture for the exhibition “America at Home” for the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair. Sixteen architects were invited to design rooms for the exhibition showcasing new American designs, and architect George Howe, who designed Philadelphia’s PSFS building on Market Street, invited Esherick to take part. Howe’s room was called “A Pennsylvania Hill House,” and its design captured the mix of modern and rustic style that was emerging in places like Bucks County in the middle decades of the 20th century. Esherick’s contributions to the exhibition included a sofa from the Bok house, the famous spiral staircase, a five-sided hickory table, and cherrywood wall panels. This exhibition represented the first time that Esherick’s work was seen by a wide-ranging public. Lousie V. Sloane, who was in charge of publicity for the “America at Home” display, wrote in a letter to Esherick that “The ‘Pennsylvania Hill House’ is a very popular room with visitors… and the stairway continues to bring forth exclamations, questions and comments from those who go through the building.”

By his later years, Wharton Esherick was known among colleagues and admirers as the “Dean of American Craftsmen.” His work would eventually earn him a retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts and Design) in 1958, and a Gold Medal from the New York Architectural League. His work is included in the collections of the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Whitney Museum of American Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. One legacy of Esherick’s earliest years working with wood—and a renewable form of accessible art—are his printed holiday cards.

When he was first settling in Paoli and exploring his new surroundings, he made prints that captured the seasons, and his snow-covered scenes of houses and hills were very popular when he made them (and they still are today.) One such print, called “January,” appeared in The Century Magazine, and other prints of his were published in Vanity Fair and The New Republic. “January” depicts a person walking up a road blanketed with snow, with a single blackbird perched on a nearby fence, and four more circling overhead. Using the end grain of a block of wood to create the image, he carved away much of the lower third of the print to leave a pillowy expanse of pristine snowfall. It has an air of mystery, with frost disguising the landscape underneath, and the figure faces away from us. Looking at this image now, it seems quite modern for 1923. And in 2020, there’s something uncannily familiar about it. This holiday season, marked in so many ways by the COVID pandemic, means that many of us have carved out small groups to celebrate with, and some of us will celebrate solo. It feels strange, and it’s not easy. Esherick’s print is not overtly “Christmas-y,” and contains no text, but its single figure with his neighborly birds sends us a timely and powerful message. The only thing to do, especially in the cold and unknown, is to walk straight ahead.

“January”, 1923, wood engraving by Wharton Esherick. Image courtesy

of the Wharton Esherick Museum.