Until the beginning of the 20th century, American Chestnut trees—perhaps as many as 4 billion of them—swept across a vast region of the eastern United States like a sash. Their historic range could be traced from New England to Pennsylvania and Ohio, southwest across West Virginia, North Carolina and Tennessee, and down to the northern parts of Georgia, Alabama and Louisiana. Builders and furniture makers prized the straight-grained wood, which is rot-resistant, light, and easy to work with. Farmers harvested chestnuts each year to fatten up their livestock, and local wildlife fed on the mast. Chestnut wood is all around us: when it was plentiful, it was used to make railroad ties, houses, furniture, and musical instruments. Generations of Americans ate chestnuts themselves, as well as meat and dairy products from chestnut-fed animals.

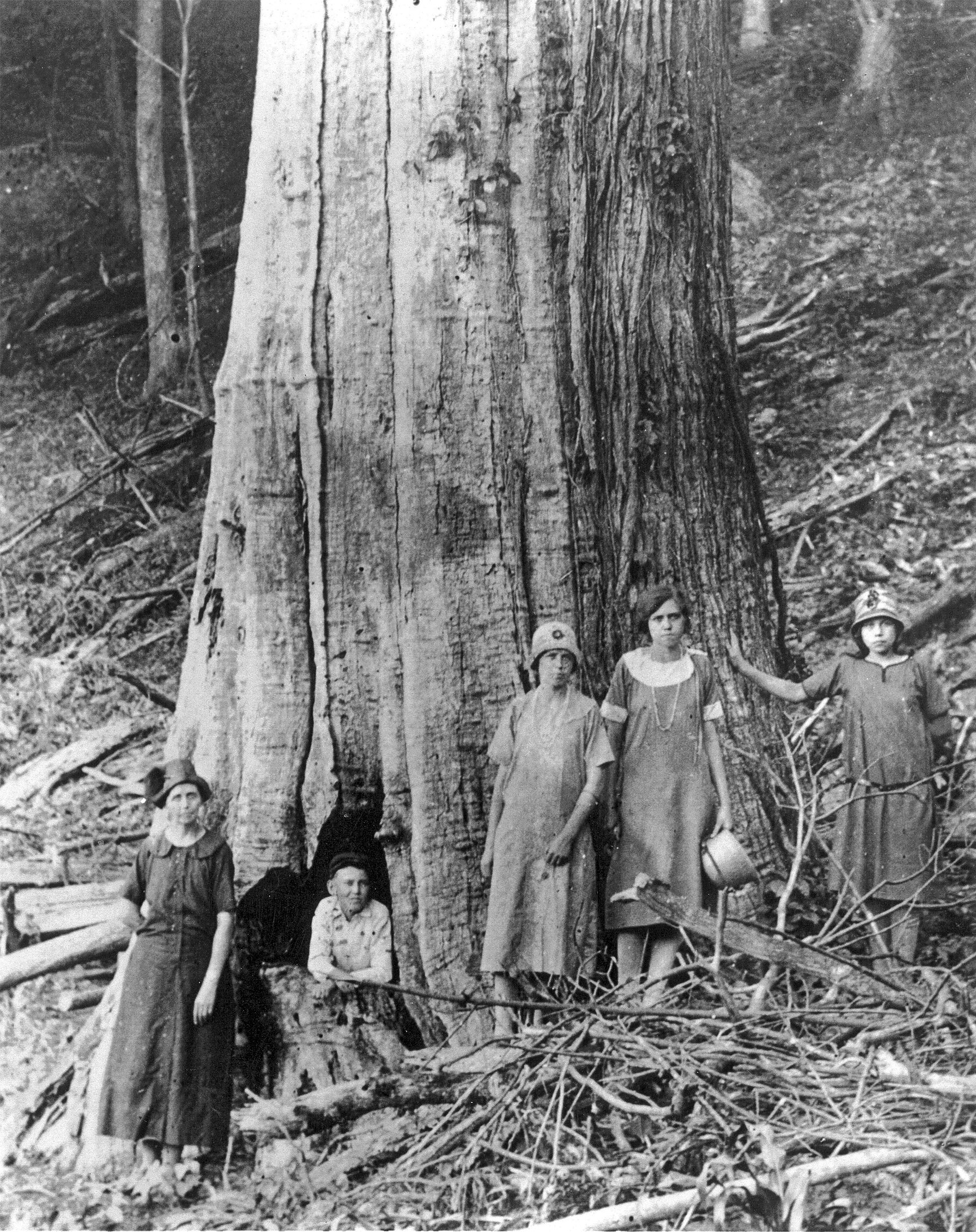

Wild American chestnut trees growing in Western North Carolina.

Tanners used the bark’s natural tannins to cure their leather. For centuries, castanea dentata supported an entire regional ecosystem, particularly in Appalachia. In the Blue Ridge Mountains, the trees’ white catkins made the landscape look as though it had been blanketed by snow when they began to bloom each summer. Prior to European colonization, people from the Shawnee and Cherokee tribes mixed chestnuts—which are both starchy and high in protein—with corn to make bread. The black bear population feasted on chestnuts before hibernation, and sheltered under the trees. According to the American Chestnut Foundation, about 200 million acres between Maine and Mississippi were once covered by chestnut-dominated forests. But to see a living American Chestnut tree today, you’ll have to travel to northern Michigan to find the extreme edge of their historic range, or the American Chestnut Foundation’s research arbors. What happened to the American Chestnut tree? And why is its catastrophic demise it such a little-known story?

One reason might be that it occurred over a century ago, and the story has passed out of living memory. Changes in the way we live and eat mean that reliable, frost-resistant, productive trees are less important to the average American now than proximity to a good grocery store. And today, walking around midtown Manhattan during the holidays, chestnuts in little wax paper bags can be purchased from street vendors, who roast them so that their earthy fragrance fills the air. But the chestnuts that come from street vendors—immortalized though they may be by Nat King Cole’s “A Christmas Song”—are not American at all. They’re most likely imported from Italy, where the castanea sativa, or “sweet chestnut,” has been cultivated since Roman times. Chestnuts of various species are accessible to us today thanks to global trade. But our native castanea dentata population, along with the wood, bark, and nuts they produced, and the lifestyle and customs that grew up around it, were all but eradicated by the middle of the 20th century. And it started, of all places, in New York City.

Chestnut blight devastation photographed in 1943.

The fungus that would ultimately come to be known as the American Chestnut Blight was first documented in 1904 at the New York Zoological Park, now the Bronx Zoo. A forester at the park reported that an astonishing number of chestnut trees on the grounds were dying for no obvious reason. Research would later reveal that a pathogen called cryphonectria parasitica had arrived in North America with a group of Japanese Chestnut saplings around 1900. Asian chestnut trees had long been exposed to the fungus and were immune, but castanea dentata was defenseless. Trees began dying in New York and Pennsylvania. In 1910, a Southern Lumberman editorial made reference to "mysterious blight" that appeared to be affecting chestnut trees. Foresters in Pennsylvania began burning dead trees and spraying those that were infected but still appeared healthy, to no avail. By 1925, cryphonectria parasitica reached the Great Smoky Mountains. Appalachia was hit especially hard by the blight because the region was so rural. The populations of game animals like racoons, squirrels, grouse, and wild turkeys that had once fed on abundant chestnuts were now decimated, and the Great Depression was just a few years away. Now two important food sources, the chestnuts themselves and the animals they fed, were in peril.

The blight continued apace during World War II and the postwar era, in which processed, shelf-stable food flooded the American marketplace. Fewer and fewer families, even in rural areas, were self-sufficient, and more people were consuming store-bought food. It’s possible that even if the chestnut trees had survived, the shift in consumption habits would have steered people away from consuming chestnuts and the small game animals and livestock that had fed on them. Today, the only way to find chestnut wood in significant quantities is through salvage operations like ours. The Hudson Company is fortunate on occasion to find well-preserved 19th century barns in Ohio, Pennsylvania and Maryland whose wood can be reclaimed and repurposed.

A Large Surviving American Chestnut Tree in Kentucky.

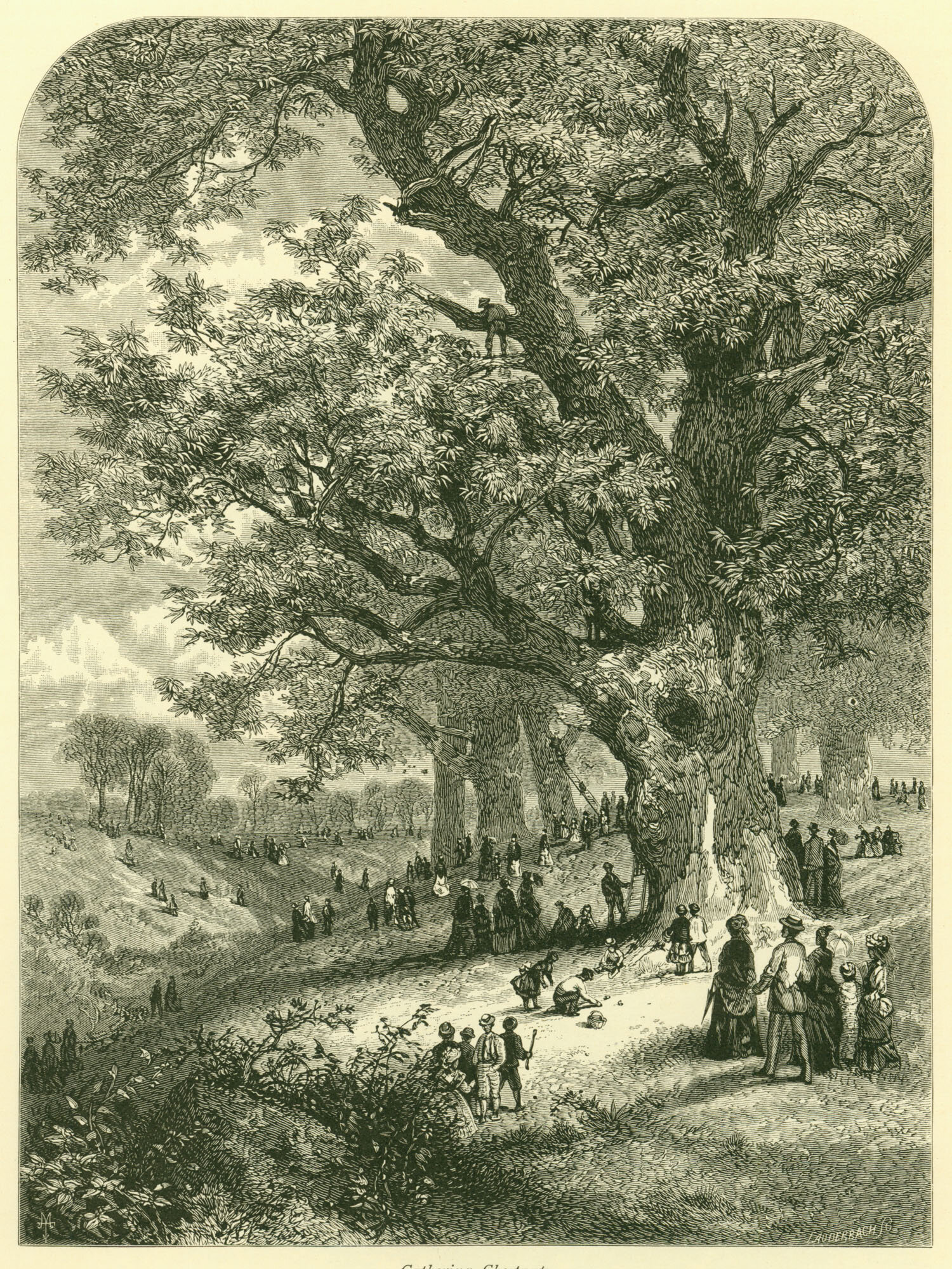

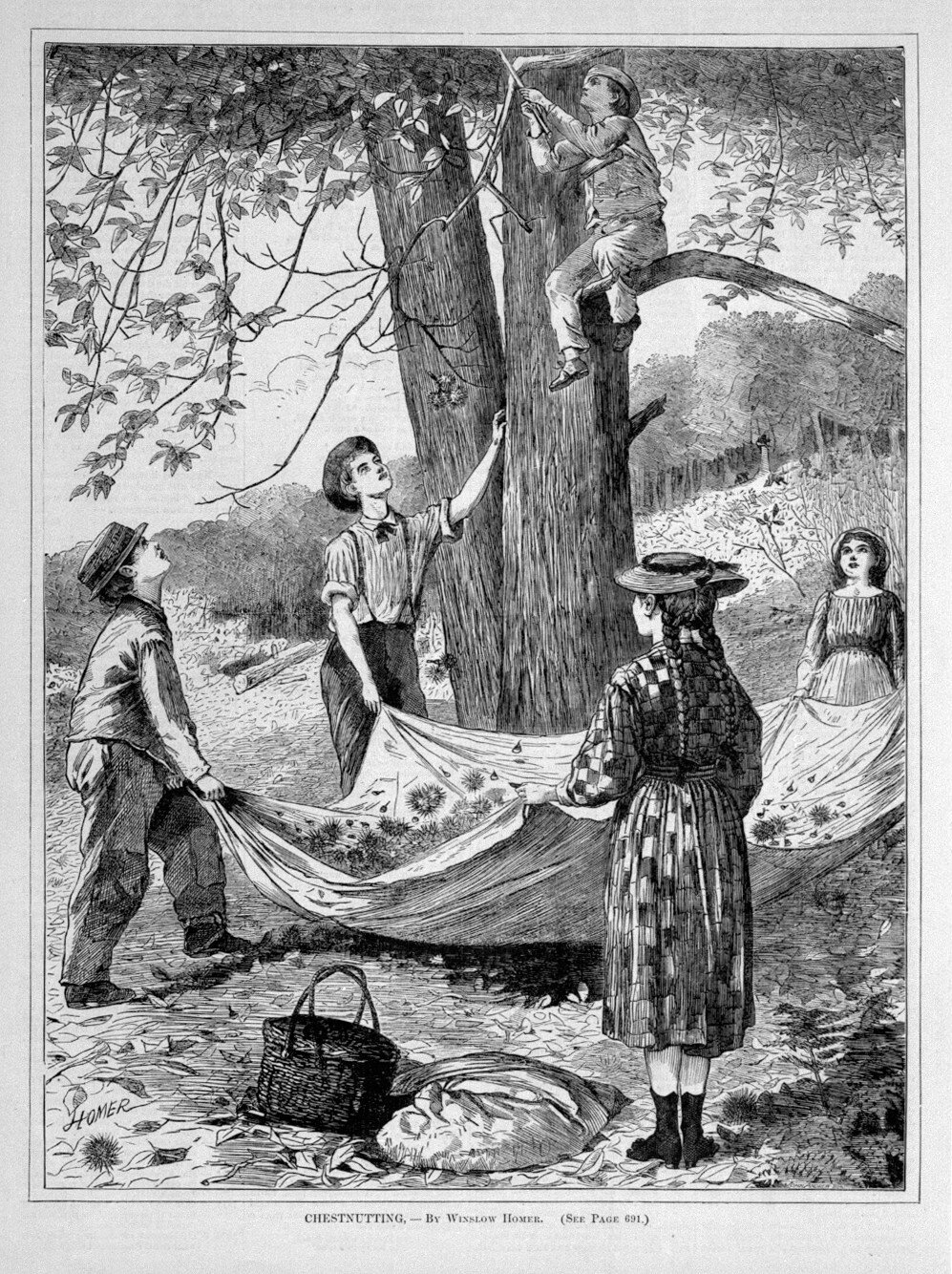

Drawing of a chestnut tree by James Fuller Queen.

Writing in The American Chestnut: the Life, Death and Rebirth of a Perfect Tree, Susan Freinkel notes that chestnut was often used in concert with other hardwoods like oak, cherry, or black walnut. The finest 18th and 19th century American furniture you’ll encounter in great collections like those at the Philadelphia Museum of Art or the Metropolitan Museum of Art, contains many chests, desks, tables and chairs made primarily from mahogany, walnut, poplar or cherry, with pieces of chestnut used strategically in various places for support. In furniture, chestnut tended to be a supporting player, but as timber, it was unmatched.

Some chestnut wood is described as “wormy” chestnut, which would seem to belie the trees’ imperviousness to insects. But wormy chestnut has a very particular origin: when trees began to die during the blight but were still upright, the larvae of the chestnut timber borer beetle made its way through the wood. When that wood was salvaged, it appeared to have holes and lines throughout, which initially made it undesirable. But as the Colonial Revival movement gained popularity in the 1940’s and ‘50s, wormy chestnut became fashionable as a wood for furniture, floors and trim for people seeking a distinctive rustic look.

Reclaimed Chestnut Kitchen Island.

Reclaimed Chestnut from The Hudson Company

Reclaimed Wormy Chestnut Writing Desk.

For those who love the American Chestnut and want to see the trees flourish again, genetic engineering holds great promise. Founded in 1983 by three botanists, the American Chestnut Foundation, based in Asheville, North Carolina, now has chapters in 16 states. The ACF’s mission is to use genetics to try to give American Chestnut trees some of the immunity of Chinese chestnut trees through cross-breeding. With each generation, additional crosses increase the amount of Chinese chestnut DNA in the American trees, which scientists hope will give these “perfect trees” a fighting chance.